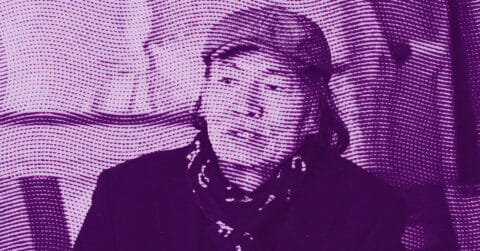

Listen to me carefully, you bunch of snobs: this young Thai man who covers the walls of New York with his black holes before triumphantly returning to Bangkok deserves that we stop sneering for two minutes. Kantapon Metheekul, who signs as Gongkan, looks nothing like what you are used to seeing in your sanitized galleries. His work smells of sweat, nostalgia, and that kind of silent rage that builds up when you find yourself stuck between two worlds without being able to choose.

Born in 1989 in Bangkok, Gongkan followed the classic path of the good student who ends up in advertising, that slow death of the creative soul. But unlike so many others who rot there, he had the courage to leave everything behind for New York, that city that crushes dreamers by the dozen. Three years fighting, sticking his stickers in the subway, painting black portals on walls, before realizing that the real battle was elsewhere. Returning to Bangkok, he didn’t bring back a shiny American diploma, but something much more precious: a vision.

The legacy of Dali or the beauty of anxiety

When Gongkan states: “I am inspired by Salvador Dali, through his use of intense colors to evoke a feeling of thoughtful introspection; surreal and silent moments in time that are both beautiful to look at but charged with hidden anxieties”, he is not just citing a convenient influence [1]. He establishes a lineage worth dwelling on because it reveals the deep mechanisms of his own pictorial language.

Salvador Dali, that flamboyant Catalan born in 1904, built his work on a similar tension between seductive surface and troubling depth. The Spanish master developed his famous paranoiac-critical method to draw from his unconscious, creating “hand-painted dream photographs” where realistic objects are irrationally juxtaposed [2]. Gongkan follows this path but brings it back to the essential: human figures, gradual skies, and those haunting black holes that serve as portals.

The color palettes of both artists reveal a disturbing kinship. Dali used beiges and blues to create surreal contrasts, lifeless yet captivating desert landscapes. In Gongkan, one finds the same gradients ranging from dark blue to light green, deep violet to pink then pale yellow. This airbrush technique combined with brushstrokes creates a dimension reminiscent of Dali’s Spanish skies, those expanses that seem both infinite and claustrophobic.

But whereas Dali paints melting time, Gongkan paints impossible displacement. His characters don’t wait for the soft watches to tell them it is too late; they jump into the void. Gongkan’s black holes function like Dali’s soft clocks: symbols of fluidity in a world that claims rigidity. Except that while the Catalan questions the nature of time, the Thai man interrogates that of space, territory, belonging.

This aesthetic lineage hides a fundamental difference of intent. Dali sought to visualize his personal unconscious, his erotic obsessions, his intimate fears. Gongkan, on the other hand, paints for all those who feel trapped, discriminated against, stuck in a body or a society that does not suit them. His unsmiling characters, these flat and graphic figures that emerge or disappear into portals, embody a collective anxiety. The artist himself says: “Teleport Art comes from my depression, my personal experiences, and societal issues around topics like gender inequality and human rights.”

Gongkan’s surrealism is not that of free play or aesthetic shock. It is a surrealism of survival, where the fantastic becomes the only possible way out against an unacceptable reality. His water basins that gradually replace black holes in his recent work function as distorting mirrors, reflective surfaces that never show what one would want to see there. “What you see is only the tip of the iceberg,” he warns. Beneath the soothing surface of his pastel colors lie poverty, corruption, and discrimination against the LGBTQ community.

The weight of the Garudhammas

If Gongkan deserves serious attention, it is also for his ability to transform social critique into image without falling into flat didacticism. His work Gender Equality And Righteousness directly attacks one of the most persistent hypocrisies of Buddhism: the structural inequality between monks and nuns.

Theravada Buddhism, the dominant religion in Thailand, imposes on bhikkhunis (nuns) rules called “garudhammas,” literally “heavy rules,” which place them in a position of perpetual inferiority compared to monks [3]. The first of these rules stipulates that a nun ordained for a hundred years must stand up and respectfully greet a monk ordained that very day. These eight rules, whose authenticity is contested by many researchers who see them as later additions to the original canon, have served for centuries to discourage the ordination of women in Asia.

Gongkan explains his approach: “This work criticizes the gender inequality found in the basic principles of Buddhism and other religions. Equality and righteousness are vital parts of fundamental human rights, yet in many religious ideologies, unfortunately, they are not extended to women. This work depicts how women are supposed to be pure but will never reach the higher realms of Buddhism because of their sex.”

Attacking Buddhism in Thailand is like spitting on the flag during a national parade. But Gongkan does not engage in easy provocation. He paints, with his soft colors and clean shapes, contradictions that nobody wants to see. The image of the Buddha appears in his work not as an untouchable icon, but as the silent witness of a system that has betrayed its own principles of equality.

The Buddhist theory of the “five obstacles” stipulates that a woman must be reborn as a man before she can properly pursue the Eightfold Path and reach perfect Buddhahood [4]. This doctrine, taught for centuries, creates an ontological inferiority of women. Gongkan does not philosophize about these issues; he paints them. His water basins become metaphors for this limited depth of human perception, where what is seen on the surface never reflects the structural injustices that lie beneath.

What makes his approach particularly effective is that he refuses Manichaeism. His images do not scream, they whisper. His characters do not protest, they disappear or appear. This strategy of visual silence forces the viewer to fill in the gaps, to question the absence of a smile, to wonder about these portals that promise freedom but lead to where, exactly?

The artist grounds his critique in lived experience. Originally from the Teochew community, a Chinese ethnic group established in Thailand, he intimately knows the tensions between cultures, the contradictory expectations, the weight of traditions. His recent works incorporate Chinese motifs, those blue and white porcelain bowls that become bathtubs for his characters, creating visual collisions between cultural inheritances.

His series Introspection takes this approach even further, exploring individual psychology as a reflection of social dysfunctions. In an era where mental health issues are exploding but remain taboo, Gongkan dares to show anger, resentment, fear, suspicion. He exposes his own vulnerability, the darkest side of his mind, while creating a space for reflection for the viewer. His interactive digital installations, his psychological investigations accompanying the exhibitions, transform the gallery into a laboratory of collective introspection.

The 2025 Asynchronous Affinities exhibition in Hong Kong summarizes this approach: the idea of “good person, bad timing” applied not only to interpersonal relationships but also to relationships with places, cultures, societies. Gongkan depicts himself alongside figures of different genders and races, creating a narrative feeling without ever providing enough information to complete the story. This technique leaves the viewer in a state of productive uncertainty, exactly where critical thinking begins.

The art of vertical displacement

So here it is. Kantapon Metheekul is neither the new Dali nor the Asian Banksy, and fortunately so. He builds something else: a visual language that speaks of inner migration, social claustrophobia, impossible freedom. His black holes and water basins are not graphic gimmicks, but existential propositions. They pose a simple and terrible question: where to go when nowhere is livable?

What makes his work necessary is precisely that he refuses consolations. His colors are beautiful, yes, but this beauty promises nothing. His characters find portals, but no one knows what awaits them on the other side. This brutal honesty, wrapped in a seductive aesthetic, creates a tension that lingers long after leaving the gallery.

The market has understood it, by the way. When Tim Cook, CEO of Apple, buys four of his canvases in one day, it’s not just because the colors are pretty. It’s because even the Silicon Valley titans vaguely feel that they too are prisoners of a system, searching for a portal to elsewhere. Gongkan’s genius is having found a form that speaks simultaneously to young discriminated Thai people and Californian billionaires seeking meaning.

But beware: if his work pleases, it is not because it offers reassuring answers. On the contrary. Each canvas reminds us that the purity demanded by religion, society, and family is a deadly trap. That the higher realms promised to the pure are lies to maintain hierarchies. That the only possible salvation passes through the acceptance of impurity, mixing, constant displacement.

Gongkan paints for those who have understood that the world will not change fast enough, that the structures are too solid, that the garudhammas will still be there in a hundred years. So he offers portals. Not to a better elsewhere, he is not naive enough for that, but to a different elsewhere. And in a world that hardens, that closes, that builds walls everywhere, painting holes becomes a fundamental act of resistance.

That is why this artist who never smiles in photos deserves better than your sidelong glances. He patiently builds a work that documents our era better than a thousand militant speeches. He paints our dead ends with an elegance that makes them bearable without making them acceptable. And if you still do not understand why it matters, maybe the problem is not him. Maybe it is you, stuck in your own hole, unable to imagine that one can get out except by climbing.

- Quotation from Kantapon Metheekul, interview with Thanarat Asvasirayothin, Made in Bed, 2021.

- Salvador Dali, “Paranoiac-Critical Method”, The Art Story.

- “Eight Garudhammas”, Wikipedia article consulted in October 2025.

- “Women in Buddhism”, Wikipedia article consulted in October 2025.