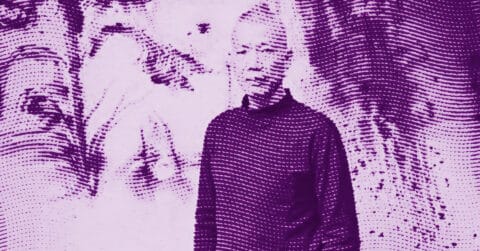

Listen to me carefully, you bunch of snobs : Nan Haiyan exceeds all your little preconceived categories about what contemporary Chinese painting should be. Born in 1962 in Pingyuan County, Shandong, this professional painter from the Beijing Painting Academy has built, over more than three decades, a body of work that redefines the contours of figurative realism in ink and color. His representations of the Tibetan peoples are neither kitschy exoticism nor tourist folklore, but a profound meditation on the human condition that finds its roots in a dual artistic and philosophical lineage.

The legacy of Millet and the spirituality of labor

The influence of Jean-François Millet on Nan Haiyan’s art goes beyond mere stylistic reference to achieve a deep spiritual communion with the ideal of social realism. As Millet saw in field work a form of secular prayer, Nan Haiyan finds in the daily gestures of Tibetans an authentic spirituality that irrigates his canvases.

When Millet painted “L’Angélus” or “Les Glaneuses”, he transformed humble workers into quasi-biblical figures [1]. This transfiguration of the prosaic finds a striking echo in Nan Haiyan’s works such as “Piety” or “Bright Sun”. In these compositions, the faces weathered by altitude and elements become the bearers of a universal truth about human dignity. Nan Haiyan shares with the French master this rare ability to grasp the universal in the particular, the cosmic in the local.

But where Millet remained rooted in the Normandy terroir, Nan Haiyan operates a geographical and cultural translation towards the Tibetan high plateaus. This thematic migration is not fortuitous: it reveals a similar quest for authenticity in a changing world. When Nan Haiyan affirms: “I paint my own feelings on this subject”, he echoes Millet’s approach which favored lived experience over academic idealization.

Nan Haiyan’s pictorial technique, a bold mix of traditional ink and Western acrylic, materializes this philosophical synthesis. As Millet had broken with the conventions of the École des Beaux-Arts to forge his own language, Nan Haiyan abandons the conceptual routines of traditional Chinese painting to explore new expressive territories. His colored impastos give the Tibetan bodies a sculptural density that recalls the monumentality of the peasants of Barbizon.

This filiation with Millet is also manifested in the choice of framings and compositions. The use of close-up shots, the monumentalization of simple figures, the primacy given to expression over anecdote: so many processes that Nan Haiyan borrows from the Millet arsenal to construct his own visual poetics. In “Prayer”, the gestural of the hand raised towards the sky directly evokes “L’Angélus”, but transposed into a cultural context where Buddhist meditation replaces Christian oration.

This philosophical kinship goes beyond the surface: it touches on a common conception of art as a revealer of social truths. When Millet showed the nobility of the humble, he prepared a change of gaze on the working classes. Similarly, Nan Haiyan, by representing Tibetans with this restrained dignity, without folklore or picturesque, contributes to a recognition of their full and complete humanity. Her realism thus becomes a political act, discreet but firm.

The twenty-five years that Nan Haiyan devotes to his Tibetan peregrinations make him the contemporary heir of this tradition of Millet of the painter-witness. His canvases function as a collective intimate journal, where anonymous faces succeed one another, carrying within them the history of a people. This documentary approach, devoid of sensationalism, is directly in line with French social realism of the 19th century.

The use of color in Nan Haiyan also reveals this deep kinship. His muted reds, earthy ochres, and deep blues evoke Millet’s palette, but enriched with the specific harmonies of the Tibetan plateau. This chromatic fidelity to the depicted environment testifies to a same demand for truth: paint what you see, without artifice or idealization.

Auteur cinema and the poetics of the everyday

The second artistic lineage that permeates Nan Haiyan’s work finds its sources in the aesthetics of auteur cinema, particularly in its ability to extract a profound poetry from the banal. His compositions function like fixed shots of a contemplative film, where each figure seems seized in a moment of temporal suspension.

This cinematic approach is first manifested in the treatment of light. Nan Haiyan handles contrasts with the subtlety of a director of photography, creating atmospheres that immediately situate the action in a specific time and place. In “Pure Land”, the grazing light that caresses the faces evokes the sophisticated lighting of a Tarkovsky or a Hou Hsiao-hsien. This mastery of illumination transforms each canvas into a virtual film set.

The framing adopted by Nan Haiyan also reveals this cinematic influence. His compositions often favor tight framing on the faces, in the manner of close-ups that allow auteur cinema to reveal the inner selves of characters. In “Waiting”, the face of the elderly woman occupies almost the entire surface of the canvas, creating a troubling intimacy with the viewer. This forced proximity generates an immediate emotion that goes beyond simple representation to achieve pure empathy.

The influence of cinema can also be read in the narrative construction of his works. As auteur films favor ellipsis and suggestion over the explicit, Nan Haiyan constructs his compositions around suspended moments, unfinished gestures, gazes lost in the void. These “dead times” in painting create a space for projection for the viewer, who mentally completes the suggested narration.

The series of mothers and children by Nan Haiyan functions particularly according to this cinematic logic. Each canvas could be the freeze-frame of a feature film devoted to Tibetan motherhood. The tender gestures, the complicit gazes, the protective attitudes: everything contributes to creating a visual grammar of maternal love that finds its equivalents in contemporary auteur cinema.

This cinematic dimension also explains Nan Haiyan’s particular use of the background. Unlike the Chinese pictorial tradition, which often favors neutral or stylized backgrounds, he constructs his sets with the precision of a set designer. Mountains, meadows, traditional architectures: each contextual element contributes to the construction of meaning, creating an emotional geography that firmly anchors the action in its specific environment.

The particular temporality of his works also reveals this affiliation with auteur cinema. His characters seem to be captured in moments of eternity, as if time had suspended around them. This temporal dilation, characteristic of contemplative cinema, transforms each canvas into a meditation on duration and impermanence.

The influence of cinematic editing can be perceived in the way Nan Haiyan organizes the elements of his compositions. Like a director arranges his shots according to a precise narrative logic, the painter distributes colored masses and volumes according to a sophisticated visual rhythm. In “Songs that Evoke Memory”, the alternation between areas of sharpness and blur creates an eye movement that guides the reading of the work according to a predetermined path.

This cinematic approach allows Nan Haiyan to go beyond the simple ethnographic portrait to construct a genuine visual universe. His Tibetans are not mere models posing for a painter, but natural actors evolving in their authentic environment. This naturalness, achieved through his repeated stays in the region, gives his works a rare documentary credibility.

The influence of auteur cinema is finally manifested in the treatment of silence and stillness. Like great filmmakers know how to use pauses to create emotion, Nan Haiyan builds his compositions around moments of contemplation and meditation. His characters seem inhabited by an intense inner life that shows through their concentrated expressions.

An artistic synthesis in the service of the universal

The greatness of Nan Haiyan lies in his ability to merge these two artistic heritages, the social realism of Millet and contemporary cinematic aesthetics, in service of a coherent and personal artistic vision. This synthesis is not superficial eclecticism but a deep expressive necessity.

His artistic journey testifies to this constant search for authenticity. Initially trained in traditional Chinese techniques, he has gradually broadened his expressive palette to incorporate contributions from Western painting. This evolution does not constitute a betrayal of his origins but a methodical enrichment of his means of expression.

The international recognition of his work, materialized by his awards and exhibitions, confirms the relevance of this synthetic approach. His works speak simultaneously to lovers of traditional Chinese art and Western collectors, proof of their ability to transcend cultural divides to reach the universal.

The recent evolution of his work towards Nepalese and Indian themes reveals the artistic maturity of Nan Haiyan. Far from being confined to a Tibetan specialization, he explores new geographical and cultural territories while retaining his approach method and artistic philosophy. This thematic expansion testifies to an intellectual curiosity that keeps his art in constant evolution.

His influence on the young generation of Chinese painters confirms the historical relevance of his approach. By showing that it was possible to reconcile tradition and modernity, East and West, academism and innovation, Nan Haiyan has opened new paths for contemporary Chinese art.

The spiritual dimension of his work, never ostentatious but always present, probably constitutes the most troubling aspect of his art. In a world dominated by consumption and superficiality, his canvases offer islands of meditation and depth that recall the primary vocation of art: to reveal the invisible within the visible.

Ultimately, Nan Haiyan stands as one of the essential links between traditional Chinese art and globalized contemporary expressions. His work constitutes a bridge thrown between eras and cultures, demonstrating that authentic art knows neither borders nor temporal limitations.

- Shao Dazhen, a renowned art critic, analyzes Nan Haiyan’s realist techniques in his commentaries on the evolution of contemporary Chinese ink painting, particularly highlighting his ability to integrate Western techniques while preserving the spirit of traditional Chinese painting.