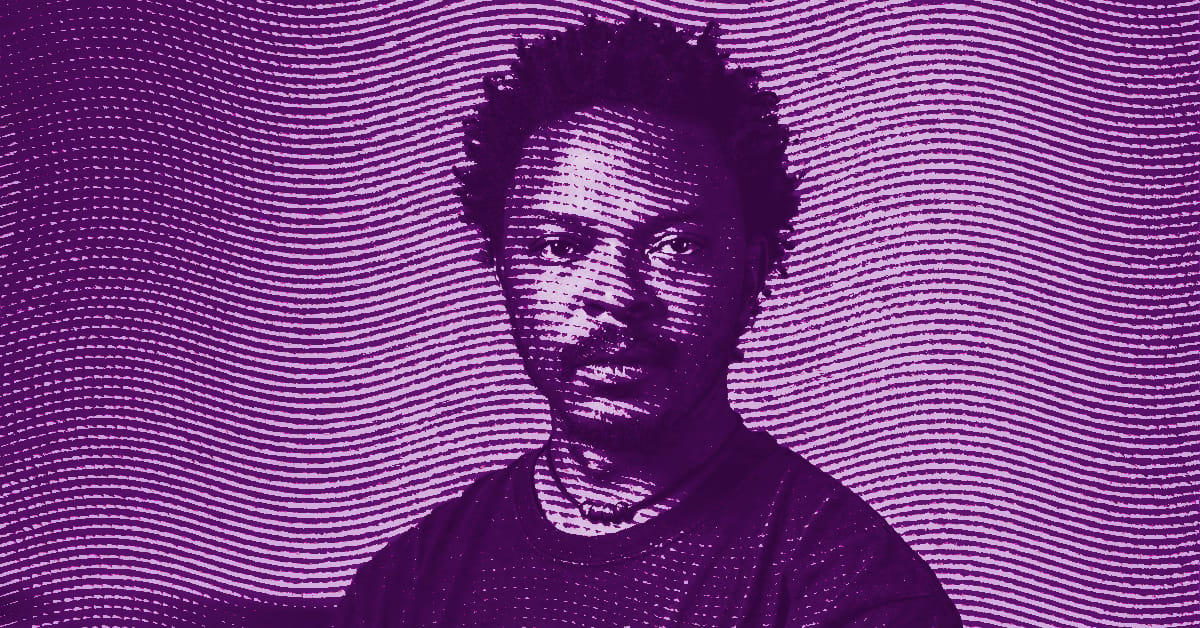

Listen to me carefully, you bunch of snobs: while you marvel at the latest contemporary art installations, a man born in Lubumbashi has been carrying out work of fierce intelligence for two decades that should shut you up. Sammy Baloji is not one of those artists who flatter the eye. He is one of those who disturb, who unearth, who force you to look at what you would rather forget. A trained photographer, graduated in literature and humanities before specializing in video and photography at the École Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs de Strasbourg, this man has made the colonial archive his battleground and the memory of Katanga his salutary obsession.

His work does not merely aestheticize ruin or document desolation. He performs a far more violent gesture: he superimposes times, confronts images, puts the Congolese present face to face with its colonial past, as one would force two adversaries to look each other in the eye. His series Memoire (2004-2006) inaugurates this radical method: photographs of colonial archives come to haunt his own shots of abandoned industrial sites in Katanga. The result is a poetic brutality that leaves one speechless. But let us not be mistaken… or rather yes, let us be mistaken together about the nature of his gesture, for it is neither nostalgia nor mere denunciation. It is a visual archaeology that uncovers the layers of violence inscribed in the landscape itself.

Architecture as an instrument of domination

Let us start with what is glaringly obvious but that no one wants to see: architecture. For Baloji, colonial architecture is never a mere picturesque backdrop or a relic to be contemplated with that condescending distance reserved for exotic ruins. It is the primary tool of domination, the language of stone and concrete through which the Belgian colonial project was written. When Baloji films the decrepit buildings of Yangambi in Aequare. The Future that Never Was (2023), he does not simply show crumbling walls. He shows how these structures continue to condition the lives of Congolese people, how contemporary workers still occupy the same spaces as their colonial-era predecessors, performing the same gestures in the same places, prisoners of a spatial geometry inherited from violence.

Belgian colonial urban planning in Congo, particularly in Lubumbashi where Baloji grew up, followed a logic of spatial apartheid that architectural historians have well documented [1]. The city was created ex nihilo in 1910, organized around the principle of racial segregation with its famous 500-meter “sanitary cordon” separating the European neighborhoods from the African townships. This distance, supposedly justified by health considerations related to malaria, actually drew a map of the colonial hierarchy embedded in the very ground. Baloji stated that he lived his “childhood in a city entirely organized around the industrial reality and the exploitation of mining resources.” This city is Lubumbashi, formerly Élisabethville, cathedral of copper and monument to the glory of Union Minière du Haut-Katanga.

In Still Kongo I-V (2024), Baloji deploys a strategy of remarkable subtlety. He frames archival aerial photographs showing the Congolese forest in 1958-1959 in afzelia wood frames adorned with motifs inspired by Belgian Art Nouveau. This apparently decorative gesture conceals a considerable conceptual violence. Art Nouveau, the style that made Brussels famous, was initially called “Style Congo” in reference to the Congolese materials and motifs that inspired it. Thus, here is the full circuit of extraction: resources leave Congo, enrich Europe, generate aesthetic movements celebrated as the pinnacle of Western refinement, before returning in the form of frames that encase the images of the very destruction they caused.

The colonial buildings that Baloji photographs and films are not mere passive witnesses of history. They are active agents in perpetuating colonial structures. The neo-Romanesque Lubumbashi cathedral, built in 1921, deliberately blocked the view of the park and the governor’s residence from downtown, physically marking colonial power in the urban space. The worker housing estates built by Union Minière du Haut-Katanga formed autonomous entities with housing, schools, and dispensaries, totalitarian micro-universes where the company controlled every aspect of workers’ lives. This paternalistic architecture, which intended to be benevolent, was just a refined form of social control.

Baloji understands that colonial architecture is never neutral. It embodies a philosophy of domination that persists far beyond formal independence. Urban plans, street layouts, the arrangement of public buildings, all continue to structure the daily existence of Congolese people according to logics inherited from oppression. When he juxtaposes Congolese plants and copper cartridge cases transformed into flower pots by Belgian households in his installations, he reveals how even European domesticity participates in the extractivist chain. Copper torn from Katanga, forged into shells during the First World War, then recycled into decorative objects in Belgian bourgeois homes: here is the obscene life cycle of a material that carries within it the memory of multiple violences.

The philosophy of invention and destruction

If architecture is, for Baloji, the visible language of domination, it is philosophy that one must turn to in order to understand the epistemological mechanisms that made this domination possible. The artist does not cite philosophy by chance in his works. In Tales of the Copper Cross Garden, Episode I (2017), he intertwines images of a copper foundry with excerpts from the autobiographical writings of Valentin-Yves Mudimbe, Congolese philosopher and poet whose monumental work The Invention of Africa (1988) revolutionized the understanding of knowledge about Africa [2].

Mudimbe showed that Africa as it exists in the Western imagination is a construction, an invention produced by a colonial discursive apparatus that included anthropology, cartography, the civilizing mission, and natural sciences. What Mudimbe calls the “colonial library,” this collection of texts, classifications, and maps that defined Africa from the outside, finds its visual equivalent in Baloji’s work. The photographic archives that the artist exhumes and reactivates are precisely the instruments of this “invention”: they were used to catalog, classify, essentialize the Congolese, reducing them to ethnographic specimens.

Baloji’s artistic gesture is deeply in the spirit of Mudimbe in its approach. He does not seek to oppose a “true” Africa to an invented Africa, but to reveal the very mechanisms of this invention, to show how the tools of colonial knowledge, photography, geological mapping, and urban planning maps, contributed to the construction of an Africa available for exploitation. The colorful geological maps he presents in Extractive Landscapes (2019) are not mere technical documents. They are tools of power that divide the Congolese territory into extraction zones, reducing it to its mineral resources, erasing all historical and cultural depth to retain only the market value of the subsoil.

Mudimbe also emphasized the role of the Catholic Church in the colonial enterprise. Missionaries did not come only to “save souls”; they actively participated in the project of reshaping African subjectivities. Baloji captures this dimension with remarkable acuity. In Tales of the Copper Cross Garden, the choral chants that punctuate the images of the foundry are not a simple musical counterpoint. They evoke the young Congolese singers holding copper crosses before their chests, a symbol of double extraction: that of the metal and that of the soul. As Baloji put it with sharp clarity: “Nothing less than the copper crosses held before the hearts of the altar boys suggests how missionaries attempted to steal their souls while exploiting local copper resources for the benefit of Europeans”.

The Congolese philosopher had grown up in a colonial seminary, an experience that nourished his entire work. Baloji, for his part, grew up in a factory town entirely dedicated to mining extraction. Both deeply understand how colonialism did not merely exploit resources: it sought to reshape consciences, impose new categories of thought, and destroy local systems of knowledge to replace them with Western taxonomies. The copper crosses of Katanga that Baloji exhibits, objects that served as currency between the 13th and the 20th centuries, testify to a sophisticated economic and symbolic system prior to colonization. The arrival of the Union Minière du Haut-Katanga rendered these crosses obsolete, reducing them to mere ethnographic curiosities.

This destruction of local value systems in favor of Western market logics is at the heart of Baloji’s work. When he presents precious fabrics from the Kingdom of Kongo transformed into bronze and copper “negatives” in his series Copper Negative of Luxury Cloth Kongo Peoples (2017), he performs a gesture of symbolic reappropriation. These palm raphia fiber textiles, with a fineness comparable to velvet, circulated in European cabinets of curiosities before being relegated to the status of ethnographic artifacts. Baloji literally recasts them in Congolese metal, as if to reverse the process of decontextualization and reification they have undergone.

The philosophical dimension of Baloji’s work also lies in his refusal of any nostalgia. He does not seek to restore a mythical precolonial past, which would be falling into the trap of essentialism denounced by Mudimbe. On the contrary, he works in the interstices, in the gray areas where past and present, archives and contemporary creation mingle. His installation Gnosis (2022), presented at the Palazzo Pitti in Florence, featured a giant black fiberglass globe surrounded by reproductions of historical maps of Africa. The very title, “Gnosis,” directly refers to the subtitle of Mudimbe’s book: Gnose, philosophie et ordre de la connaissance. Baloji knows that the question is not to produce a “true” representation of Africa that would correct the false colonial representations. The question is to understand how regimes of truth are produced, how orders of knowledge are established that render some knowledges legitimate and others inaudible.

Towards an ethics of memory

So what does Sammy Baloji do, essentially? He practices what one might call a critical archaeology of the present. Each of his works is an excavation that brings to light the layers of violence, extraction, and destruction that constitute the very ground of Congolese modernity. But unlike the classical archaeologist who exhumes to better museify, Baloji exhumes to reactivate, to make these buried histories active in the present. His images are not inert documents: they are devices that force the gaze, that compel recognition of the continuity between the colonial past and contemporary forms of neocolonial exploitation.

The cobalt and lithium that today power our mobile phones and electric cars come from the same Katanga mines that produced copper yesterday for the electrification of Europe and uranium for the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. This obscene continuity, Baloji makes visible in Shinkolobwe’s Abstraction (2022), a series of screen prints that superimpose samples of Congolese uranium and images of nuclear explosions. The message is brutally clear: the atom that razed Hiroshima came from Katanga. The energy that powers the Western “ecological transition” rests on the same extractivist logic that has destroyed Congo for more than a century.

Baloji offers no comfort, no easy solutions. His work is uncomfortable because he refuses redemptive narratives. He does not celebrate African “resilience,” that catch-all concept beloved by Westerners to avoid discussing historical responsibility. On the contrary, he shows how colonial structures continue, how architecture keeps constraining, how extractivist logics are renewed under new guises. The workers of Yangambi still occupy the same buildings, carry out the same botanical classification tasks according to the same protocols as in the colonial era. The so-called independent Congo remains caught in the nets of a structural dependency that no longer has a name.

Yet, it would be wrong to see this work as a mere exercise in denunciation. What Baloji builds, work after work, is an ethics of memory that refuses both forgetting and fossilization of memory. His archives are not there to feed resentment or foster complacent victimization. They are there to illuminate the present, to allow an uncompromising understanding of the mechanisms that continue to operate. As he himself stated: “What interests me as an artist is how we create an alternative discourse, how we tackle these modes of thought established since the colonial era and identify their limits, their weaknesses.”

Perhaps this is Baloji’s most radical gesture: not just to denounce colonial discourses, but to seek their flaws, their points of fragility, the gaps through which other narratives, other orders of knowledge can emerge. His work as co-founder of the Lubumbashi Biennale since 2008 is part of this same logic. It is not simply about exhibiting Congolese artists, but about creating the intellectual and institutional infrastructures that will allow these artists to produce and disseminate their works on their own terms, without going through the filters and validations of the Western art market.

The radicality of Sammy Baloji lies in this methodical patience, this researcher’s rigor placed at the service of an artistic vision that never compromises on complexity. He does not simplify, he does not spectacularize, he does not make colonial horror an aesthetic consumer product. His works demand time, attention, an intellectual effort that many viewers are not willing to provide. Too bad for them. Baloji does not work for the comfort of the Western public. He works to exhume a memory, to give body to a history that one would like to keep buried under the rubble of colonial buildings. And in this excavation work, he perhaps accomplishes one of the most necessary tasks of contemporary art: forcing us to face what our modernity owes to barbarism, and what our prosperity continues to cost others.

- Lagae, Johan, “Rewriting Congo’s Colonial Past: History, Memory, and Colonial Built Heritage in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of the Congo”, in Repenser les limites : l’architecture à travers l’espace, le temps et les disciplines, Publications de l’Institut national d’histoire de l’art, 2017

- Mudimbe, Valentin-Yves, The Invention of Africa: Gnosis, Philosophy, and the Order of Knowledge, Présence africaine, 2021 (original edition in English: Indiana University Press, 1988)